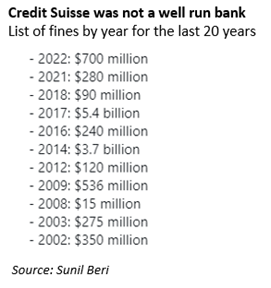

I normally write these notes on a Friday morning. Since my last missive another bank – Credit Suisse – has failed. The first bank to go, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) in the US, reminded me a lot of the Northern Rock failure here in the UK. A mid-size bank, highly specialised in a certain area became subject to a classic bank run as its area of specialisation fell out of favour and depositors (understandably) wanted out. Credit Suisse has echoes of Bear Stearns. A larger, more storied bank is pushed into a forced marriage with a bigger rival (JPMorgan in Bear’s case, UBS for Credit Suisse). The problem for Bear Stearns, like Credit Suisse, was less a classic bank run and more worries about problems with the balance sheet and a stream of legal liabilities on the way.

After the Bear Stearns’ sale in early 2008, the market actually rallied into the summer and then – as I won’t have to remind anyone – things got a lot worse very quickly. Is this the right playbook here? Equities in the US and Europe have risen this week. Credit Suisse had been a source of concern and bad headlines for years now and – as I wrote last week – its market implied probability of default for the next 12 months was sitting around 50%. Just since 2021, Credit Suisse paid $0.5bn after issuing fraudulent bonds in Mozambique, lost $5.5bn lending money to Archegos (a hedge fund) and puts its clients into a fraudulent $10bn trade finance scheme. It was comfortably the worst run bank you have heard of. Finding a solution to the Credit Suisse problem should be – assuming UBS is that solution – a positive.

One view has been that central banks will keep raising interest rates until something breaks. It looks like it is the banking system that is starting crack. My three things this week are my three observations on where we are with the banks:

- First, I don’t think this is 2008 all over again. Crises tend to become scary precisely because (like Covid) they are new and people just don’t know what to do to deal with them. Bank failures are very well understood and after 2008 we are much better prepared for all this. Banks are (much) better capitalised and banking regulators are more experienced and more prepared to be proactive. There will be more problems to come – some medium sized banks like First Republic in the US look to be in the same place as SVB for example – but this should not turn into the credit crunch/financial collapse that was 2008.

- A second reason why this time should be different is that after 2008 a lot of risky lending (for example on commercial real estate or development loans) switched out of banks and into private markets. These private market investors are often locked up in long term (10 year plus) vehicles, do not face mark to market pressures and are well placed to ride out any recession. We will need these private market lenders to stay open for business but credit markets are generally more diversified away from banks than they were in 2008. This is a good thing.

- That said, many banks are tightening their lending standards precisely to avoid the sort of troubles we are seeing today and we saw in 2008. You can add this to the list of reasons (including higher energy prices and mortgage rates) that will mean consumer spending will slow. A growth slowdown and some sort of recession still looks more likely to us than any sustained reacceleration in inflation. We continue to like safer bonds as the investment opportunity here.

Finally, and you can stop reading now if credit market mechanics are not your thing, what happened with Credit Suisse was actually pretty interesting. It is worth noting that the bank did not go bust but was technically sold to UBS for CHF3bn. Earlier in the week, on the Wednesday before the sale, the Swiss authorities gave a CHF50bn funding package to help keep Credit Suisse going. The terms of this were enough that a CHF17bn subordinated Additional Tier 1 (AT1) bond was written to zero when the sale went through. CHF17bn is a lot of money! And it was more than twice the value of Credit Suisse on the Friday before the sale.

It is very unusual to see equity investors get paid and bond investors get zero. AT1s were put in place after 2008 precisely to deal with the sort of situation Credit Suisse got into. How it was resolved has been pretty controversial though and the UK and EU have put out statements that they would not have been as harsh on bondholders if equity investors were getting paid (as they were here). The AT1 market is a pretty important source of financial support for banks. On Monday we saw a sharp sell-off in AT1s for many European banks. Since then we have seen a recovery helped in part by the public support from the UK and EU authorities. We are continuing to watch this market closely – a collapse of confidence in AT1s would probably not make the headlines but would not be good at all for the health of the banking system.

For those that don’t know, I head the investment team at IPS Capital. Each week I highlight a few things that have come across my desk that I think are interesting and investment related. We always welcome dialogue so if you have any questions we’ll be happy to answer them.

Chris Brown

CIO

IPS Capital

cbrown@ips.meandhimdesign.co.uk

The value of investments may fall as well as rise and you may not get back all capital invested. Past Performance is not a guide to future performance and should not be relied upon. Nothing in this market commentary should be read as or constitutes investment advice.